This modest contribution comes at a time when Tunisia

is trying to find its way to a true democracy, equitable growth and dignity for

its people. Youth joblessness in general and the unemployment of university degree holders

in particular, were the main fuel of the Jasmine Revolution. Unless the true underlying causes

are identified, all prescribed solutions, no matter how ingenious they are,

won’t produce the collectively desired results. This short document, attempts to

show that the key underlying cause, and thus Tunisia’s Achilles’ heel, is the poor

structure of its industry. The analytic National Innovation System (NIS)

framework is used to tackle this enduring and complex problem. Standard

indicators, spanning the main components of the NIS, are used in an attempt to debunk the culprits,

and initiate a collective curative process for our ailing society.

Introduction:

On the 14th

January 2011 the free people of Tunisia

forced their corrupt ruler from power, and collectively willed to build a

modern peace loving democratic society. On the 23rd October 2012

they confirmed their historic choice and held their first successful democratic

elections. The on going Jasmine Revolution, punctuated by these two key dates,

was a spontaneous ideologiless, leaderless and peaceful awakening claiming

social and economic justice. It was energised by people’s thirst for dignity,

peace and democracy, the chains breaking words of our poets and prayers seeking

divine blessings for our martyrs that either gave their blood for freedom or

died awaiting a loaf of bread. These unprecedented events sparked the Arab

Spring, and inspired the Occupy Movement.

Despite the

success of the elections, the relatively democratic political process and the

support of the international community, Tunisia is still struggling, among

others, with high unemployment, significant regional inequalities, and

increasing corruption. It goes without saying that this enduring state of

affairs is the result of almost half century of autocratic leadership,

exacerbated by an unduly erratic two years post revolution transition. In fact,

as these words are being written, the head of the Troika government presented

his resignation, after failing to constitute a small apolitical government

staffed with technocrats, in the aftermath of a strongly condemned first and

hopefully last political execution.

These

successive government failures, attest to the incapability of the political

leadership, in and out of the government, to apprehend the most urgent

problems. They kept talking about several issues such as security, national and

regional growth, and employment, without offering any viable actions or plans

to gain the trust of the population, and start alleviating the social pressure.

The last two years downward spiral, leading to a grotesque cold-blooded

political assassination, was accelerated by a relentless struggle for power,

futile populism, and an absence of willingness

and/or competence to debunk the true underlying causes of the crises. As a matter of fact, and at best, almost all

deployed actions and programs were reminiscent of the pre-revolution

government!

The youth

joblessness crisis was the telltale of a lingering systemic failure, a

persistently ticking time bomb that was consistently ignored, in favour of

restricting freedoms, intimidating citizens, and looting the country, but

theatrically tackled with make-believe policies. This unemployment state of

affairs was characterised by a seemingly absurd but symptomatic high percentage

of jobless university degree holders. As a mater of fact, and for the last

decade or so, the more educated the job seeker was, the lesser chances she/he

had to find a job! This counterintuitive situation will be referred to as the

Tunisian Paradox.

A Post Revolution vision:

Post revolution Tunisia

has a unique and a historic opportunity to intelligently leverage its competitive

advantages and swiftly catch up with the developed world, while simultaneously taking

the lead in becoming a Sustainable Knowledge Society (SNS). This long-term vision stipulates that Tunisia secures its place on the

world stage as a Knowledge-based society where Innovation-led sustainable

growth, creative and skilled entrepreneurial human capital, and democratic

political system, pave the way towards economic and labour force

competitiveness, equitable and inclusive national and regional sustainable

growth, along with the betterment of local and global well being. It is

interesting to note, that the underlying causes of the Jasmine Revolution, the

Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement are symptomatic of the same social ills,

making of Sustainable Knowledge Tunisia

an experiment worthy of attention for the rest of the planet.

In order to achieve the above vision Tunisia has to

espouse, more than ever, a systemic approach where the four pillars of the

Knowledge Economy (KE) are harmoniously combined, in time and in space. To swiftly

and robustly converge to the above stated vision, it is necessary to create a

innovation friendly environment for the efficient creation, dissemination, and

use of knowledge through a proactive Economic and Institutional Regime,

to provide educated and skilled population that is able to effectively use

knowledge through a high quality, flexible and responsive Education System,

to facilitate effective communication, dissemination, and processing of

information via a modern Information and Communication Technologies (ICT)

infrastructure, to stoutly pursue the connection and assimilation of global

knowledge, the adaptation and creation of local knowledge for the socioeconomic

benefit via a viable National Innovation System (NIS).

While the above four pillars of the KE are

necessary for the foundation of a successful knowledge-based economy, they

remain insufficient as to the attainment of a sustainable society. In order to

secure sustainability it is fundamental to further characterize the Knowledge

Society (KS) we will be building in general and the type of innovations we will

be producing in particular. In this framework, economic growth, social cohesion

and environmental protection must go hand in hand making sustainable

development an integral part of policymaking. The complementary KE and

Sustainability dimensions integrated within a systemic framework require suitable

governance and institutional cybernetic architecture capable of the required,

steering, monitoring and coordination functions.

Obviously, it is far from enough to have a

vision, a strong willpower to pursue it and even a unique window of opportunity

to launch it, if the minimal socio-political, institutional and material substrates

are not available! In fact, Tunisia

is a country with scarce natural resources, limited ST&I policy making and

R&D management experiences, and almost inexistent and at best inoperative ST&I

coordinating and monitoring institutions. Therefore, for Tunisia to

swiftly and progressively converge to this vision, it has to secure the

adherence of all stakeholders, clearly seek and devise polarizing strategic

growth sectors with a portfolio of growth flag ship initiatives within a global

and coherent long-term development action plan.

Strong economies have usually relied on three

polarizing major sectors, i.e., armament, space and health. However, small countries, such as Tunisia, with scarce

natural resources, small market, slowly receding cheap labour, and a relatively

strong highly skilled base, has the potential to successfully engage in high vale added sectors and technologies, while investing viably

in areas for its strategic security, e.g., agriculture, energy, and water.

In order for the above vision to succeed and

thus lead to sustainability, it is necessary to work towards the establishment

of a sustainable consumption and production society whose sustainable

performance is measured by appropriate indicators such as its footprint. Simultaneously, Tunisia has to zoom initially into

eco-efficient technologies and move progressively but surely to green-innovation

with a strong and dynamic entrepreneurial engagement consolidated with

aggressive public investment. To do so, and build resilience against

disturbances, Tunisia needs

to urgently build capacity and acquire the proper know-how, methodologies and

tools especially evidence-based policy analysis and design, strategic planning

and management, foresighting for development, NIS reorientation and priorities setting, and

roadmapping for technology and innovation.

Invigorated with this vision and the needed

viable strategies and action plans to attain it, the Tunisian people will be

able to regain hope, trust their leadership and work hard while looking forward

to better future for themselves and their children. Nevertheless, this is only

possible if the political context is ripe for such an undertaking. While

preparing the necessary foundations to launch this vision, and gain as much

grounds for the successful implementation of this few decades’ long complex

process. The present government, with the support of the opposition and all

concerned institutions should agree on an inclusive post revolution compact,

abstain from political power games, and guarantee the following three necessities:

(i) security, (ii) jobs for the youth and (iii) rebooting the economy. An

attempt to implement a similar project, was initiated by the previous head of

the government, and immediately aborted by the main political party, whose

General Secretary is nothing but the initiator!

An Innovation System in the

Making:

A Three Millennia Innovation Legacy:

During the last three millennia, Tunisia

has been an exceptional place for blending, disseminating and flourishing of

several civilisations such as the Carthaginian, the Roman and the Hafsids. The

openness of the country to other cultures, its ethnic and religious tolerance,

coincided with its prosperity as attested by the diversification of its markets

and trade, as well as its mastery of science and innovation.

Tunisia saw knowledge thrive during its Carthage

era. Architecture, shipbuilding, irrigation and agriculture were among many

successful sectors as attested, entre autres, by the 4th Century BC,

28 volumes Magon Treaty.

As early as the 7th Century, Tunisia

played a key role, and saw its capital Kairouan become a hub of learning and

intellectual pursuits in the Arab-Islamic world. The Great Mosque of Kairouan,

founded in 670, along with its teaching arm was a centre of education both in

Islamic thought and secular sciences. Among its old pupils and scholars Ibn Al

Jazzar an influential 10th Century Muslim physician, well known for

his “Zad Al-Musaffir” (The Viaticum) book. During the 13th Century Tunis was made the

capital of Ifriqiya. This shift of power helped the Al-Zaytouna Mosque, host of

the first and greatest university in the history of Islam, to flourish as major

Islamic learning and scholarly centre. Ibn Khaldun, a Tunisian scholar, is the

most famous among its many alumni. He is most known for his Al-muqaddimah

(Prolegomena) and viewed as one of the fathers of modern historiography.

The 19th Century Beylical Tunisia, witnessed the creation, by Ahmed Bey, of the Technical School

in 1840, and the Military College of Bardo in 1855. This effort of

modernisation was carried further by Mohamed Sadok Bey, under the influence of

his Minister Kheireddine Pacha, by the creation among others of the Sadiki College

in 1875, partly inspired from the European educational system. Ex-President

Habib Bourguiba is among his former students.

The French

protectorate era, witnessed the creation of a number of needs-driven research

instructions, among them, withy their present designations, the Pasteur

Institute of Tunis in 1893, the National School of Agriculture in 1898, and the

National Institute of Marine Science and Technology in 1924. After WWII, the

above research institutions were augmented by the Institute

of Higher Education in 1945 within the

University of Paris. Among its students, 300 Tunisians

were enrolled.

The Precursor to the Innovation System:

Independent Tunisia,

realised very early its national pressing and urgent educational and research

needs among several socio-economic ones, and swiftly responded to these

challenges by the creation of the Ecole Normale Supérieure, in 1956, and the

National Institute of Agronomy of Tunis,

previously designated as Ecole Supérieure d’Agriculture of Tunis, in 1959. These creations were

followed by the creation of the University

of Tunis in 1960. The

university included the Faculty of Science, the Faculty of Letters and Human

Sciences, the Faculty of Law, Political Sciences and Economics, The Faculty of

Medicine and Pharmacy, and the Faculty of Theology, the former Zitouna. Almost

simultaneously, the Arid Region Problems Research Centre, and the Economics and

Social Research Study Centre (CERES), were established in 1961 and 1962, respectively.

The National Engineering School of Tunis (ENIT) was created in 1969.

It is important to

note, that almost a decade after the creation of the first university in

Tunisia, it was decided in 1968, to abandon the university system, and place all

higher education institutions and national research centres under the control

of the newly created Directorate General of Higher Education and Scientific

Research (DGESES) of the Ministry of National Education. Shortly after this

peculiar and significant restructuring, it was decided, in 1972, to establish advanced

academic degrees equivalent to the master’s level, launching accordingly the

Graduate Studies in Tunisia.

The latter

restructuring and creation dynamics, along with the increasing numbers of the

academic staff, allowed the creation of some research laboratories and several

master’s degrees programs in several academic fields. As a consequence, the

number of students grew, and prompted the creation of several higher education

institutions first in Sousse

and Sfax, in 1974, and Monastir and Gabes in 1975.

These accelerated

development, led to the creation, in 1978, and for the first time of a

dedicated scientific research ministry, dubbed the Ministry of Higher Education

and Scientific Research (MHESR). Not only did this ministry inherit and expand

the mission of the DGESRS, but did also acknowledge the nature of the

development phase of the research system and the need to build capacity and

thus keep higher education and academic research closely connected.

Tunisia’s Innovation

System Today:

The landmark event

that launched the Tunisian scientific Research System was the promulgation, in

the 31st of January 1996, of the Orientation Law concerning

Scientific Research and Technological Development. This founding legislation

was the result of the creation, in February 17, 1991 within the Prime Ministry

of the Secretariat of state for Scientific Research upgraded in February 17,

1992 to the Secretariat of State for Scientific Research and Technology (SERST).

The focus of SERST was research activities oriented towards socio-economic

development, while basic research and graduate education remained with the

Ministry of Education and Science.

Formulated within the NIS framework, the Orientation Law’s main

objectives were:

- Reinforcing coordination between the different components of the NIS in order to create the necessary synergy, to build enduring competencies, and to ensure a sustained financial support,

- Promoting capacity building as the key pillar of the NIS, as well as technological innovation,

- Increasing progressively R&D expenditure, while ensuring diversity of financial resources and reinforcing private and international contributions,

- Promoting innovation and technological development through the support of innovative companies, the valorisation of research results, the reinforcement of partnership between research an industry, as well as the creation of techno-parks and incubators,

- Reinforcing follow up and evaluation of research activities and structures,

- Developing international cooperation in order to facilitate the exchange of best practices, to access international scientific excellence networks, to benefit from international financing, and to be an active contributor to human knowledge,

Shortly after, a

number of institutions reminiscent of modern National Innovation Systems were

created and/or added to the existing ones, within and/or under the tutelage of the

Ministry of Higher education and Scientific Research (MHESR), and the Ministry of

Industry and Technology (MIT). As stated in the above objectives, these institutions

were to insure the execution, the monitoring and evaluation of the activities

stipulated in the Orientation Law and its subsequent implementation decrees.

The current NIS is made of the

following main components, grouped in the standard four different levels:

Level 1: High level

policy

- The Higher Council of Scientific Research and Technology,

- The High Level Committee for Science and Technology,

- The National Consultative Council of Scientific Research and Technology,

Level 2: Ministry

- Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, (the Directorate General of Scientific Research (DGRS), is the main funding body for scientific research),

- Ministry of Industry and Technology.

Level 3: Agency

- The National Evaluation Committee of Scientific Research Activities (CNEARS),

- The National Observatory of Science and Technology (NOST),

- The National Agency for the Promotion of Research (ANPR),

- The National Institute for Standardisation and Industrial Property (INNORPI),

- The Agency for the Promotion of Industry and Innovation (APII).

Level 4: Research and Innovation Performers

- The Universities and Public Research Centres (Tunisia’s R&D system is composed of about 140 research laboratories, 500 research unit, evolving in 13 Universities, as well as 33 public research centres, 8 technical centres, and 10 technoparks.)

- Business enterprises and private research institutions (The industry in Tunisia is made of almost 6000 SMEs having 10 or more employees, of which 2 800 are totally exporting ones, 1975 with foreign participation, 1221 are 100% foreign owned, and 1679 are totally exporting SMEs.)

In order to energise the NIS and facilitate the emergence of synergies

among its different subsystems, a number of R&D programs and financial

instruments were deployed since 1992. Among these the Federated Research

Program (PRF), the National Research and Innovation Program (PNRI), the

Valorisation of Research Results Program (VRR), and the R&D Investment

Premium (PIRD). The capital-risk mechanisms, especially the SICARs (Société

d’Investissment à Capital Risque), was amended in 2009 to encourage further

risk-taking.

A Performance Preview of the

Innovation System:

Education, scientific research and innovation

sectors had always a place of choice in Tunisia’s development strategy.

This comes as recognition of their essential role in the country’s development.

According to the World Bank data, Tunisia’s

spending on education in 2008 was 6.3% of GDP, which is clearly higher than Algeria (4.3% in 2008) and Morocco (5.4%

in 2009). In 2009, 34.4% of the

corresponding population benefited from tertiary education (Algeria: 32.1% in 2011, Morocco: 13.2%

in 2009). According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report

2011-2012, Tunisia

ranks 24th as to primary education enrolment and 40th regarding

its quality. Moreover, the same report ranks the overall quality of the

educational system 41st, and the quality of math and science education

18th. It is however unfortunate to note that Tunisia was much better ranked last

year!

R&D expenditures saw a steady increase

during the last decade. They more than doubled, going from 0.5% in 2000 to 1.1%

in 2009. While this performance remains unmatched in the region, i.e., 0.1% for

Algeria in 2005, and 0.6%

for Morocco

in 2006, it fails short from responding to the needs of the country to move up

the value chain. The number of researchers in R&D, per million people,

almost tripled during the last two decades. Indeed, the indicator went from

about 700 in

1998, to 1.9 thousands in 2008. This performance remains notable in the region

when compared to 170 for Algeria

in 2005 and 661 for Morocco

in 2008. Concerning scientific and technical journal articles, Tunisia managed

to exponentially outnumber its neighbours and reach 1022 publications in 2009,

while it merely published 91 articles in 1993. Comparatively, Algeria published

123 article in 1993 and 606 in

2009. However, Morocco

saw its 164 publication of 1993 reach only 391in 2009.

This resulting exponential publications growth is

directly due to the major restructuring that took place following the

promulgation of the 1996 Orientation Law. As a matter of fact, a closer inspection

of these dynamics, especially in well established academic fields such as

chemistry, shows without any doubt, the cause and effect relationship between

the promulgation date of this legislation and the ensuing publications renewal.

According to Thomson Reuters in 2011, the number of publications per million population,

makes of Tunisia the leading

country in Africa, as well as ahead of Saudi Arabia.

A large number of these publications were

published as a result of collaborative research work between the Tunisian researchers

and their main colleagues abroad. Africa Global Research Report published by

Thomson Reuters in April 2010, reveals that Tunisia

had 32.6%, 2.8%, 2.7%, 2.5% and 2.1% of its publications with France, USA,

Italy, Spain and the UK respectively. These results are

analogous to Algeria’s,

showing the similarities between the neighbouring countries, but strikingly

different for Egypt that not

only collaborates with the USA

and the UK, it also does

with Germany, Japan and Saudi Arabia. It is worthy to note

that these statistics will most certainly change in favour of the Tunisian

German cooperation, since an ambitious bilateral research and innovation

cooperation program was launched for the first time as early as the beginning

of this year.

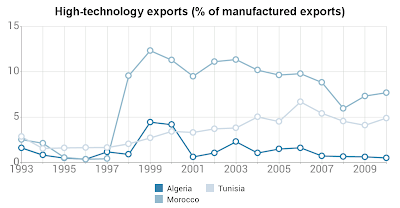

This relative performance of Tunisia is unfortunately offset by

the modest contribution of R&D to the Tunisian economy. For instance, The Tunisia:

Economic and Social Challenges Beyond the Revolution report by the African

Development Bank, reported that only 17 international patents were granted by

the USPTO and EPO to Tunisia during 2001-2010, and 22 for Morocco. This

observation is corroborated by the low high-technology export, performance. Indeed,

Tunisia exported 4.9%, in

2010, while Morocco

achieved a 7.7%. These results are a revelation of a breakdown in the Tunisian

NIS, despite the noticeable evolution of the number of researchers, engineers

and scientists and scientific and technical publications. It is obvious that

these contrasted performances between Tunisia

and Morocco,

notwithstanding the marked differences, in favour of the former, in the

indicators above, is an indication of structural differences, which took place

in 1997, downstream the respective innovation chains!

Again, the far from satisfactory performance of

the innovation system is clearly confirmed in the 2011-2012 Global

competitiveness Index, where Tunisia

scores just a poor 3.6 in

innovation, and a 3.8 in

technological readiness, yielding a score of 3.9 in the innovation and

sophistication index. Moreover, A low company spending on R&D score of 3.4,

along with a weak university-industry collaboration in R&D index of 3.7,

explain the low 3.4 capacity for innovation of the Tunisian SMEs.

Shortcomings of current policy

responses:

The

revolution was the ultimate expression of a systemic failure, an outcry of a

desperate population that conquered its fear and ousted a corrupt police state

that could no longer control it. The telltale of that failure was a lasting

blatant youth joblessness crises characterised by a seemingly absurd but

symptomatic high percentage of jobless university degree holders. As a mater of

fact, and for the last decade or so, the more educated you were the lesser

chances you had to get a job! This counterintuitive situation is nothing short

from a Tunisian Paradox.

The key

shortcomings, regardless of corruption and lack of freedom, which contributed

to this state of affairs, are:

•

Lack of a collective

vision,

•

Despite the

isolated successes, the “system” didn’t deliver,

•

Lack of global

coherence, and absence of coordination, led to a systemic failure,

•

Despite industrial

modernization programs, innovation remains frail,

•

Absence of

synergies even with the multitudes of incentives and programs.

Recommendations:

The above acknowledged shortcomings and challenges

are indeed an opportunity for Tunisia

to find its pathway for deep transformation. Consequently, facilitating its

ascension to the rank of developed nations, and transforming its NIS to catch up with the frontier

countries.

In this final section, a number of short and

medium terms recommendations are made:

Higher

Education System:

- Grant autonomy to the leading universities, within a healthy differentiation program,

- Reshape university governance by adapting best practices and structures compatible with high quality education and research training,

- Allow the universities to diversify their funding by maximising returns while playing their role as a local engine of socio-economic growth and development,

Industry

System:

- Adopt a long term industrial policy capable, in the short and medium terms, of consolidating the competitive sectors, while launching progressively a dozen of high value added niches within a coherent strategy,

- Initiate national innovation procurement programs, to accelerate the implementation of the industrial policy,

- Champion a number of targeted large national ST&I projects to enhance capacity, encourage collaborative work, and boost collective learning,

Governance:

- Create a Vice Prime Minister position to coordinate the complex ST&I system, and insure its alignment with the remaining national policies and strategies,

- Streamline the structure of the actual NIS with confirmed models while keeping the same components and slightly modifying their missions and roles,

- Built effective and sufficient capacity due regards ST&I policy analysis and design along with R&D management capabilities.

Prof. Jelel Ezzine

President of the Tunisian Association

for the Advancement of Science,

Technology and Innovation (TAASTI)